Pt. 1: The Death of Jampa Choden

The sign on the rust curdled iron gate read, “वेनेरेबल जाम्पा चोडेन। एक मानिस अहिले विगतमा छ, तर केवल पछि मात्र बिर्सिए। बुद्ध अवतार को लागी एक उम्मेद्वार। 1980”. Translation, “Venerable Jampa Choden. A man now past, but only much later forgotten. A candidate for the Buddha incarnate. 1980” He was the only such person to elude my interview. It was his lifestyle as a hermit of the Himalayas which saw him inaccessible for the likes of myself, an American journalist abroad. I had traveled all over Asia interviewing people who were venerated by others as our contemporary incarnation of the Buddha. It is said that if you meet a self-proclaimed Buddha on the side of the road, you should kill him, for he is an imposter. However, if you meet a man who is thought to be the Buddha in the minds of many, then that individual might just be something more. Now present at his funeral procession in the foothills of Nepal, I was one of many in a foreign party of travelers, tourists, and journalists.

Above us, a clear thinly stretched sky of blue and white lay peaceably on a bed of distant, and joyously snow-capped peaks. Beyond the gate, our feet pattered up the smooth ancient cobblestone of the monastery yard. The bare feet of the monks slapped the bald stone in droves. The breaches of the picketed fence offered only fragments of the children playing beyond it. They kicked tatter-flapped soccer balls and ran blissfully past the long line of attending men and women in their sheathed garb. The sustain of mesmerizing tones emanated from the strikes of various brass alloy bowls which littered the courtyard and surrounded the front gate. Under the brilliance of the sun, they aspired to a fine shimmer of gold. The ebbs and flows of their various tones pacified those solemnly present and washed away somber eyes. I stared ahead quite fixated on the entranceway before me. The monastery was of an old stone construction with glassless windows and wooden accents. I slid my hand over the rusted fixtures of the rot-ridden mahogany door, the brass handles coated in a thick powder filth and bright teal-green oxidation.

Chanting emanated through the aperture of the dark corridor before me. There was an enigmatic aroma that pierced the melancholy ambiance. As if it were in the air we breathed, pain flooded our chests as we entered the smoky darkness of the ancient structure. Cast rays penetrated the ceiling through the haphazard stone cradles of light above. Eyes gleamed through the soft spiraling of blush red dust and emotion. The windswept breaches above released low roars and vivacious whispers. Aromatic anger and dingy infinite disgust permeated the cavernous labyrinth of these filthy, straw-laden hallways. In a single file, we shuffled past the stone archway of the ceremonial gathering chamber. The stale dust perturbed only by the audible gasps and wails of women who sobbed and wept. His eternal stillness smote the hearts of those present for his laughter no longer beckoned their appraisal. He was said to be a man so wise that he knew only how to laugh and to love.

There was an ever-present rustle of crimson pulu and sheathed silk. The reluctantly crossed legs of the sangha were supported only by a starkly haphazard stone floor; cracked and uneven. It is said that a lotus can’t grow from stone and that there is nothing more elegant than to imagine that it could. On that day, under the stoic, sprawling eye of the Himalayas, it was we together who became the stone-birthed lotus of ten-thousand folds. A wavering sea of raised right palms expelled fear from the graven chamber with their mudra; the Buddha’s personal token against existential dilemma. Emotions were present over the silence illustrating the depth of his grasp on all whom he touched.

The body of Jampa Choden lay still before all. As if to be risen, whimsical particulates climbed the solitary band of light that illuminated the altar beneath him. The candle cast shadows of all who loved him congealed on the surrounding walls as a single dancing entity. The vibrating dark mass was more him than those who composed it. Impermanence’s crimson, blood rusted dagger birthed cleavage in the hearts of all those present. Glassed eyes rested fastidiously upon the bright gleaming corpse. His leathery unfurrowed brow now washed in the morning sunlight. His hands lay crossed above his abdomen and his empty satchel upon his chest.

The satchel paid homage to the local tradition of carrying no-things. Only once a brittle dryness had befallen the goat’s skin was it then immersed into a mixture of Indigo and jackfruit dyes to produce the incontrovertible sage green of the hide satchels. Like emeralds, they adorned the sides of every monk in the ceremony. Carried by a corpse, the satchel is a reminder that nothing possessed can be carried into the afterlife. It wreaked of futility and spelled out the inevitability of death and its necessary but often reluctant acceptance.

The mystery of Jampa’s wisdom seemingly climbed the sawdust pillars that befell his corpse, like music visible in the light. A whiskey smoke emanated from the eternal flame by the crown of his head. The atmosphere of the ceremony commanded both reverence and awe. From my left was handed to me a torn page of Jampa’s book with the following underscored in thick black ink, “Death feasts on the softest of innards, the ageless clam is no longer reluctant to split.”

After the ceremony, it was announced that Jampa’s ashes would be returned to his mountain dwelling on the side of mount Kyanjin Ri in the small mountain village of Kyanjin Gompa. The pilgrimage would be a small group of mountain sherpas, townspeople, and returning monks. We departed the following morning.

A man named Ankar was assigned to assist me throughout the 5-day arduous journey. He was an old and kind man with a demeanour placid and giddy like that of a docile jackal. His teeth looked like they were lovingly dappled in place by a blind man, intertwined and overlapped like the fingers of a botched handshake. His fur hat was reminiscent of a vigorous juniper and his skin creviced like dried fruit. It was Ankar who held my hand when the air got thin and it was his smile that comforted me when there was no distinguishable path forward.

A steep mountain ridge stood rising from its alluvial bed. Its jagged supine tip raked the underbelly of the soupy mist as it descended upon us. The climb was arduous and steep. Dry snow released cold onomatopoetic expletives under my feet. Compressing peaceably as if it weren’t actually there, the lack of resistance painted it as a hallucinogenic figment amidst a beauty so unimaginable that it called into question the nature of this reality. Above the clouds, erected were only untrodden snow-capped amber and ash stone faces. The pink bulge of the dying sun splashed its hue indiscriminately upon all. Cumulonimbus clouds hid their secrets in mauve dimples and stole from the sun brilliant shades of salmon, fuchsia, and magenta. As the sun descended into its cloudy grave, its fires cremated the world before it anew. From atop that precipice I had never been more isolated, and yet I had never felt more connected with the whole of the world.

It took Jampa’s death to finally get me out here, past the pebbly riverbank and beyond the sawdust beach. This was proof to me that this man would still make the world a better place, even from beyond the grave. As the clouds filled in below us, we were now entering into the monk’s mountain dwelling. Above the clouds, splendour, below, a mystery. By this time, the world had surmised that this man was not the Buddha incarnate. With that said, it was from Jampa’s perch, high-up in the monk’s dwelling of Kyanjin Gompa, that I could then clearly see that the Buddha does indeed reside in each and every one of us.

Pt. 2: Between Death and Dust

From my left was handed to me a torn page of Jampa’s book with the following underscored in thick black ink, “Death feasts on the softest of innards, the ageless clam is no longer reluctant to split.” With a vague grasp of the sentiment, I conceded to ponder it over later and passed the page along to the curious eyes looming over my right shoulder. The high timbre of their thin whispers was abruptly silenced as the elders began to murmur to each other. As all took notice that their stillness had broken, it was as if it had instantaneously permeated throughout the room, stopping dead all present in respectful homage.

At the front of the room sat two respected Buddhist elders, Rinpoche Coliquo from Tibet and Ajahn Vijhammido from Thailand. It was my understanding that the three of these old and disciplined teachers were all once very close and largely came to form their Buddhist studies together in the same small monastery just a few hundred miles south of where we were then. They had not only made this journey to pay respect to their close and longtime friend, Jampa Choden, but also to deliver some words for him at the ceremony of his death. It was Ajahn Vijhammido, the English orator who began to speak first.

“For reasons which will become self-evident shortly, I am sure that Jampa would have rather had you all hear about yourselves and not another word about him. After All, his incarnation has now ended and yours still carry on… Here is what I know Jampa would have wanted for you all to hear, and I know because I have heard him argue these points many times before. When we were younger, I found him to be quite stubborn but as I have aged, I can now say that he was always very wise in spite of his age, it took me many years to come to these same conclusions.”

From his full lotus position on the floor, he continued,

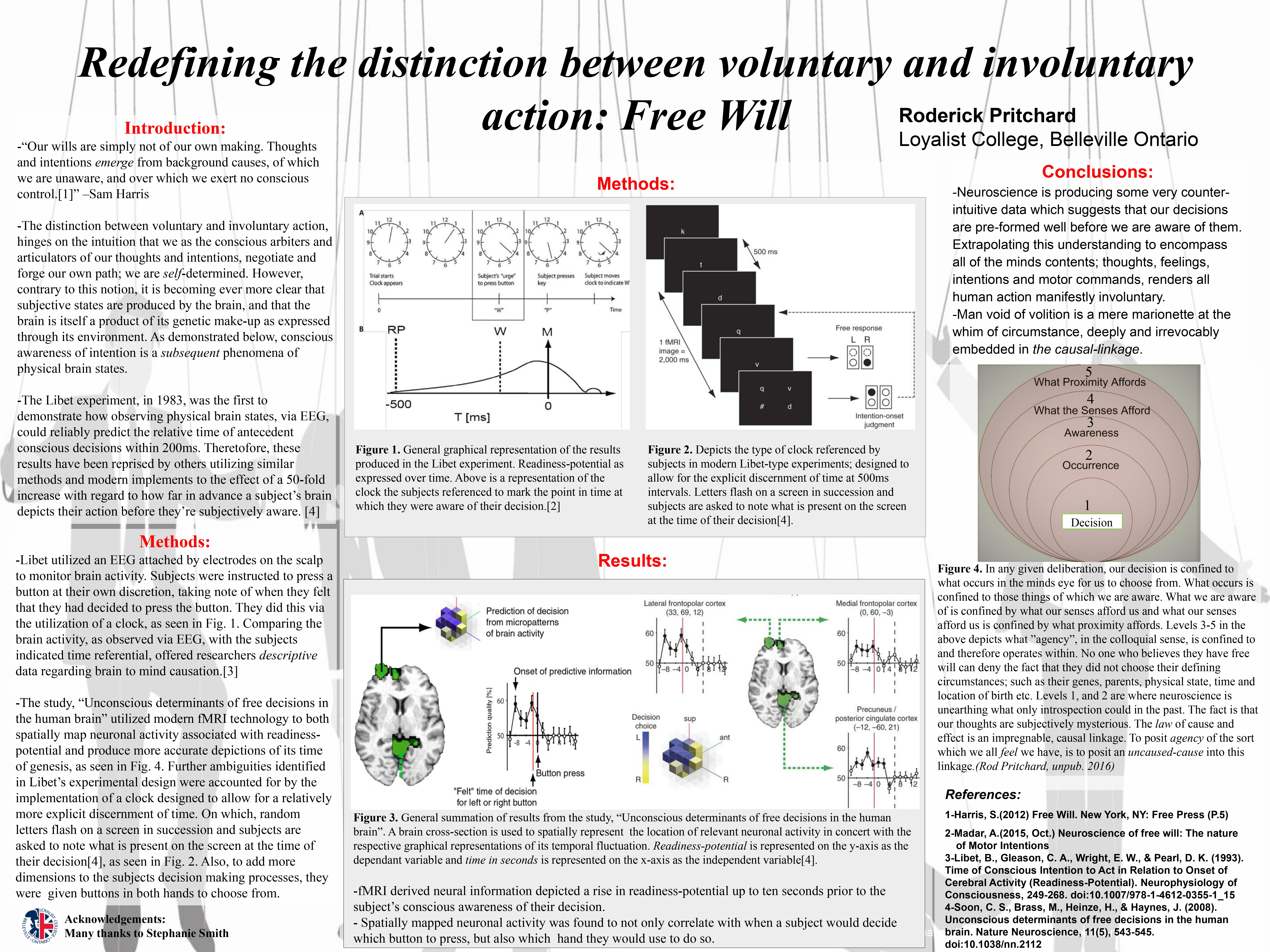

“The part of you that is experiencing this life… that part is not synonymous with the part that controls it. Some say that life is directed by choice and not by chance, but Rinpoche Choden’s response would be, “Then what are the chances that one might make a particular choice?” He was inclined to say that all choice was predetermined by chance, which then, was a function of circumstance, beyond that of an individual and their experiences, that no experience of having choice could impress itself into the determining factors of chance.

“If you compare yourself to others”, he continued. “No matter if you come out on top or not, it is, in either case, a matter of a lack of compassion in one way or the other. Comparison is a natural outcome of separation, but separation is a false conclusion, to begin with. Whether you lack compassion towards yourself, or towards others, is really irrelevant to the more central understanding that all is one. It is in light of this simple fact that true equanimity can be arrived at. This is certainly the point that Jampa would have wanted to be expressed here at his funeral and cremation ceremony.

“It was, after all, his unique interpretation of reincarnation, one in which, “what it is like to be you” and “what it is like to be me” are really the exact same experiential entity, separated only by their distinct places on the timeline of existence. We are all the same conscious fluid if you will. And I quote…” he announced, “Every life that I exit is yet another into which I enter, into which we enter. Reborn as a baby with insomnia, a totally annihilated history of past lives, narrowed to the singularity of this one present life… for when I die, a baby will inevitably be born, and it will be the same meta-phenomena of consciousness which resides in it as in all other beings… for consciousness itself is featureless.

“Only once you see that you and your enemy are one and the same, do you cease to have an enemy at all. Only once you realize that you and those that you care for, are one and the same, do you truly connect with them in a confluence of love. Jampa was a man that saw the beauty in the universe of things, just as they were, and never aspired to inject the freedom of the will into this grand image. It is larger than the life-blood of consciousness which courses through it, it is the ultimate determining factor, while consciousness, as we all experience it, is no more than one of the plethora of features of the grand cosmic play. Jampa often espoused how these understandings could convey the ultimate source of wisdom. A wisdom before which all things fell perfectly in place, to exist just as they were meant to, free from judgment, desire and aversion. He called this wisdom “the light”, it was that by which all sense could be illuminated and accepted just as it was formed.

“In a world of infinite information, we often find ourselves overwhelmed by an abundance of the irrelevant and the extraneous. Learning how to Identify what is pertinent to you and your life is a very valuable skill.

“No matter what terms you define life by, scientific or otherwise, there is always an element of uncertainty, of magic to be found somewhere in your thesis. There is always a gap or two in any theory’s completion and logical deficits to be had at every turn. Existence is nothing short of miraculous.

“I get so caught up being me that I lose sight of the oddity that is to be me, to exist at all. Being me is all I have ever known and all that I ever will. I am honestly starting to believe that you and I, we have always existed and that that’s not going to change anytime soon.

“Where there is a lack of compassion, there the universe knows itself not. Not only are we all created equal, but what exists within us is identical. To understand this is the ultimate wisdom. From wisdom, no misery can be derived and no judgment can be passed. The ego is confusion, it is a distraction. We feel as though we are each a part of the cosmos, rather, we should feel that it is a part of us and that we are all one.

“Should we see that we are one, then there are no grounds to take anything personally. In separation, we are no more than deterministically driven causal actors, or put another way, we are simply expressions of our surroundings influences, the conduit through which they pass. Just as one can come to see that there is no “self” within, they must recognize that this applies to all others too. The conventional and intuitive formula is that this point in space is affecting that point in space when really the formula is much more complex, there is one puzzle, a systemic confluence of infinite and interlocking pieces. Rinpoche Choden would say that each piece of the universal puzzle was predetermined, or to put it another way, cut on myriad angles and that it was these unique angles that determined how each of us, each piece, was to interact with all other pieces. Those who understand this are impervious to the inflictions of others. For, when I fully understand you, what you are, what I am, then no matter what our interaction may be, my reaction, my resulting expressions, my actions, are no longer tainted by your influencing actions. Those who see this truth in the world can’t be hurt by others, nor can they act on the world in unskilful ways.

“The mark of the beast is to lie. To lie is an expression of fear. This fear is derived from the misunderstanding of the fundamental nature of all things. When you catch yourself lying, know that.

“Ultimately, this world is better characterized by its ephemerality than by its solidity and conservation. Time is a gauntlet that very little survives. Not much lasts and even less matters.

“Often, it is those among us who are conventionally considered to be the luckiest, that must most face the irony of misery.

“Those of us who are lucky enough to watch our family and friends die…

“Those of us who are lucky enough to watch our skin wilt…

“Those of us who are lucky enough to feel our bodies deteriorate…

“Those of us who are lucky enough to feel our mental capacities fade…

“Those of us who are lucky enough to witness our accomplishments collapse into the sands of time…

“Each and every day those who are conventionally accepted as the lucky ones undertake the sorrow that accompanies their transient lifestyles. Constantly propped up, just to have it pulled out from under them.

His tone became surprisingly radiant and joyful as he carried on,

“The problem is that I have quite the imagination, often I confuse it with revelation and become its marionette. On the topic of Karma, Rinpoche Choden had much to say…

He continued, “The western convention of karma, that what happens to you is caused by a reciprocal universe. As if there is some higher power watching, judging, and disciplining or rewarding; an all-seeing arbiter of justice, if you will. This is clearly a western contortion of karmic principles by the influence of Abrahamic religions. You know, the ones in which there exists an omnipotent and omniscient creator god with his hands in the mix. The average westerner simply removes their god, gives the powers to the universe itself, and calls that Karma. This couldn’t be more wrong.

“To a Buddhist, karma is quite simply the recognition of causality… of determinism. Now, even under a deterministic framework, it is plain to see that it is one’s own mind which disciplines them in circumstances where they go against their principles and ethics.

“It is not the fact that you have done something wrong which hurts you, it is the fact that you know that you have done something wrong which hurts you.

“Discipline is everything. It is what saves us from unskillful action and defines skillful action. Discipline is self-rewarding and it is what forges the best possible life. Indiscriminate satisfaction is the truest form of happiness and well-being, and discipline is the straightest path to it.

“Karma is cause and effect, it is one thought leading to another, it is one action leading to another, it is one word leading to another, it is one world leading to another. Just as the present, in general, determines the future. Your current mental state is determined by your prior mental states, which in turn determine your future mental states. Coming to understand the concept of determinism is itself yet another mental state and one which can be quite far-reaching in terms of influencing future mental states. All concepts are like this to some degree.

“Those who investigate the self, sooner or later realize that they are the effect, not the cause, that they are the action, not the actor.

“You see…”, he carefully continued.

“The addition of awareness is synonymous with the subtraction of distraction. True awareness is realized in the absence of distraction. So enlightenment has more to do with the loss of mental modifications than their acquisition. Awareness is the result of dropping that which distracts you from this current moment.

“You see, the enlightened mind-state is a state of pure awareness, completely and utterly unadulterated and undistracted. The study, experience, and development of our mental faculties, as to create an overall skillful mind, is what ultimately acts as the fertile substrate from which true awareness can sprout. With that said, the enlightened mind-state necessitates transcending beyond our mental faculties, words, and concepts. Forgetting life’s description is one and the same as realizing life itself… in its most visceral and tangible form. It is direct and non-conceptual.

“The life that most people lead is very much so a dream. You see, dreams appear to have a reliability and solidity to them while one is dreaming. In just this same manner, one’s experience of waking life appears reliable, dependable, and solid until that experience has passed, it then loses its solidity and credibility in much the same way as last night’s dream. The more entangled with thought that one’s mind is, the less it actually touches that which is solid of their surrounding reality. Most are often so distracted by mental artifacts that they may as well be dreaming. Dreams, much like our thoughts, especially those of the past or future, are insubstantial relative to the reality of the here and of the now.

“The past and future are merely artifacts of the mind and any engagement with either comes at the cost of our awareness of the present moment.

“Yes, felt states of enlightenment occur in the absence of mental artifacts such as words and concepts… it is the result of pure uncontaminated awareness. It doesn’t matter what the subject of awareness is, so long as it is external and experienced fully, this creates the mind’s state of satori, of nibanna, which is itself a mental artifact of a direct and relational sort. Words and concepts, on the other hand, are indirect and semantic, they are tools that accomplish much in their domain but ultimately, only exist to impede direct experience. In other words, get away from that which separates you from your direct experience of reality… words, and concepts. In this new circumstance wherein you have a pure awareness over your external reality, then comes into fruition the new inner sentiment of enlightened awareness.

“The truth is that in the normal mind, everything culminates in sorrow, eventually.

“It is the melding of one’s mind with the universe’s, in a kind of euphoric confluence which can’t be described, only felt. This is nibanna.

“With this wisdom comes a perspective that captures the big picture. If you are having anxiety over trivial things, then you simply are not seeing the big picture, you don’t yet get it, you don’t see what this life is… what it can be.

“Let go, live a life of acceptance, nothing matters anymore, connect with reality directly, be at peace. This is how Jampa would have us center ourselves in a lopsided and unstable world.

“The general aura of amor fati that enveloped Rinpoche Choden will surely ease our burden as we move forward with the proceedings and reconvene at the fire mounds for his cremation following Rinpoche Coliquo’s delivery of these words for the Nepalese attendees. With all the grace and skillfulness of the Buddha, we thank you all for attending.

Pt. 3: The Flame of Amor Fati

Following the lead of the fleeing sangha, I stepped out of the monastery into a bombardment of eye-crippling Nepalese sunshine. In a single file, we meandered down the cobblestone path under the lush green sun-cast foliage of the monastery yard. All present remained relatively hushed until we passed the open gate of the rusted iron palisade. One by one, each person in the convoy respectfully brushed their fingertips across the engraved surface of Rinpoche Choden’s commemorative plaque.

The pathway beyond the monastery gate was little more than a sun-dried russet brown lather of monsoon mud. It was grooved with deep cartwheel tracks and yak hoof footprints. I could see the red dust of the dried path in a whirling disturbance around the feet of those before me. Though the sun had cooked the season’s rains out of the pottery-like path, the fertility of the monsoon season was still very present in the lush surrounding flora where bending branches burgeoned with fruit.

The sinuous path seemed only to mind boulders which were too large to move and trees too tall to fall. On the tail-end of an approaching curve, there was a small, derelict, stone and wood arch-bridge, it circumvented a torrent of rushing rapids and carried us to the cremation grounds through the rapid’s roar. Its wooden structure was swollen with moisture and its surface was sporadically covered in a sponge-like green and yellow moss. It was an effort to not slide down the arch of the bridge’s back with my brown, leather loafers. The monks, however, made no changes to their stoic postures, their short, deliberate strides remained at ease above the grip of their bare and hardened feet.

At the entrance to the cremation grounds, there stood a group of young women surrounded by children. At the time, I supposed that they were teachers from the local school who had brought a large party of children to take part in the ceremony. I was captivated by the collage of their young angelic faces and suddenly stunned by the gaze of one particular woman’s eyes, they glinted in the morning sunlight and I couldn’t look away. Her beauty had the perfection of a beach-smoothed stone and the intricacy of harrowing waves in crescendo.

When I finally did manage to break her spell, my eyes would be drawn back to hers right away. There was no doubting the attraction. With the deep pierce of her appraising eyes, I was reminded of a woman I once knew, a woman who struck me in a similar way. She stood by the stage at a small band show I was door-manning and even there, in a dirty dive-bar, it was as if her beauty were god’s personal art. She wore fishnet stockings and high-cut jean shorts, her hair fell in long, blonde, flowing waves around her deep red lipstick and dark eyeliner. Her beauty was simply beyond belief and there was no stopping my feet as they carried me across the dance floor to her. I’m still reminded of her more often than I’d like to admit. Sometimes when I hear the soft, depressing ambiance of melancholy music, or see a long and distant horizon. Honestly, just the sun on my face can remind me of her warmth.

The procession carried on and I soon found myself beyond the old stone stack walls of the cremation grounds. Within the high-reaching walls of this roofless structure, there lingered a stagnant odour of coal and smoke. We were instructed to remove our footwear as it was customary to be barefoot within the sacred location. The townsmen lowered the gurney, atop of which Rinpoche Choden’s body rested, onto a trellis of barkless and knotty logs. As the procession continued to enter I kept my eyes peeled for the face of the woman I had seen. It wasn’t until the two old Elder monks began to light the fire that children could be seen entering. Surely, she would come in with them, or so I thought, but still, I failed to find her.

The Monks aligned themselves in rows backing onto the nearest stone wall to the firing area. As they sat they folded and tucked their ochre robes under their crossed legs. Once sat in their noble-nonchalance, polite remarks could be heard amongst the nervousness of the crowd. For most of us, there was palpable discomfort and concern in the air.

To them, all things acquired, all things achieved and all lives lived were but shallow remnants of their egos. The suffering of the pursuit, the suffering of the acquisition, the suffering of the maintenance. These men had nothing left to lose, they had abandoned all worldly features and therefore had abandoned all fear, hope, desire, and aversion.

The monks understood deeply that one does not have possessions, but rather that what they have inevitably possesses them. As a community, they had expressed ardently for years that time was both the provider and the depriver of all things, of all relationships and that it was we ourselves that created happiness and misery around this fact. “It is down to each individual to create their own disposition to the world, it is a matter of perception.” they would say.

As the smoke started to rise, it was as if a calm came over the crowd. I felt an affable breeze sweep through the shade and across the cool surface of the stone floor beneath the soft souls of my feet. As the flames licked Jampa’s body, the air began to fill with the scent of fired flesh. Before our eyes, he began to char black as if to deflect our gaze once again.

Standing at the head of Jampa Choden’s resting corpse, Ajahn Vijhammido’s voice reverberated through the stone-walled structure, “It is the scarcity of life, or rather its realization, that is the ultimate catalyst of a life worth living. A creative and enthusiastic life awaits those who can see the finiteness of their life and the inevitability of their death. It becomes preposterous to waste even one more second. It becomes absurd to spend your time in ways which you will regret.”

In the eyes of the gathered and now gazing Nepali kin, flesh turned to ash and the crackling of wood and bone was a tangible force that pulsed through the throng. By leaping flame, the old Rinpoche’s body was reduced into the hardwood and cow patty coal on which it laid.

After our eyes had fallen upon each other, I couldn’t remove her from my mind. Though I was fully entrenched in the ceremony around me, her presence seemed to remain hidden in the backdrop of my mind. I’d find my eyes wandering through the faces of the crowd, searching hers out and to no avail. I had not traveled to Asia in the hopes of falling in love. In fact, my journey to such distant lands may have been, at least partially, motivated by the exact opposite, a desire to fall out of it. Admittedly, even after over a half-decade of adventure and myriad other lovers, I still hadn’t managed to remove my first love from my mind. She was still very present in my dreams and often I would wake up sick with her absence. I never did recover and I had, in all honesty, dismissed the notion of romantic love from my life with no future expectations of finding it ever again. I am of the belief that there are precisely two personal sources of happiness one can derive in this life; 1- finding and realizing the beauty of truly and sincerely connecting with another human being and 2- discovering the real depth in your own person. The latter I could still do and so I made it my life’s innermost objective. To have both in one lifetime, you can consider yourself lucky, to somehow cobble the two together simultaneously… Well, you must be living in a world of Wattsian physics.

“To the pain of the past and to the fertility it can provide…”, Ajahn Vijhammido continued. “To all of the new beginnings made possible only by the fact of something else’s end. To the future, we owe the past and to the present, we owe all things. Jampa’s dying wish was for you all, especially the young, to know this, to feel it within your heart.”

Pt. 4: Alternative Altitudes

Nature’s careful balance of fresh cedar and clean spruce rode the new air as it settled. The loftiness of the skylight held a bright illuminated web. A fiery-white daylight beamed past unpolished glass, a cool sinuous breeze around its open lip. The brilliance of the snow’s white was emphasized by the contrasting black of the creek. It rushed by over smooth eroded stone. I could hear its bubble and its churn.

The green of the conifer and the chalk-white of the birch. Six tall windows formed the wall to my left, a modest shrine before us. Seven closed-eyed laymen sat cross-legged and silent. Before me was a young woman wearing striped pastel slacks adorning bare feet. I could see it in her calm, that she had stillness within her. A burgundy and gold rug befit the hall. All had seemingly departed in meditation, and yet, I remained. My feet were numb, they tingled and pulsed as I untied the knot of my legs.

Like the pillars of life, the forest stood tall. I stared past it, into tranquility. Before me was a word of infinite syllables, a picture of departure. I was acquainted with equanimity and in love with her serene nature. Through the silence staggered but only the occasional soft breath.

For a series of hours, we sat as the day was replaced by night. From white to blue azure, to sangria, the room was shaded in. The glow of the candles beamed brighter, eliciting yet a deeper penetration of my eye’s lids. What was once a black and blue froth, now seethed of yellow and orange flesh. With a solitary strike of the then singing bowl, our tepid postures were broken. Bowing laymen bathed in the meaningless wisdom of the bowl’s multi-tone voice. One, two, three times their heads descended before the shrine. Last meditation at Tinando Monastery.

A few years prior to my search for the Buddha incarnate, I was a victim of my own demise. I was a journalist of war. I had spent years in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Lebanon. It was a job that was both inexplicably exciting and absolutely heartbreaking. I thought I may never be able to un-see the horrors of those wars and that my life was forever changed by them. This was a time before the term post-traumatic stress disorder was even recognized. I had no idea that I had developed a medical condition but I could nonetheless feel its weight and I knew that I had to fix myself.

It was this same period of time when eastern philosophy was first being introduced to the west. It was part and parcel of what instigated the hippy revolution of the 1970s. Communities were being built on unused farmland and gurus were being extruded from the great cultural and social machine. Amidst the wars of the world, here on our home soil, many were championing the virtues of peace and love. Before I knew it, I found myself in the aggregate of lost and hurt souls, people in search of serenity and acceptance, attributes long lost to the modern world and scarcely available, even to the most rural of communes.

It was a time of liberal drug use, mostly ganja, psilocybin mushrooms, and LSD. The memories I have from this period of my life are nothing short of spectacular. Amongst the magic and the colours, I recall deriving immense happiness from even the most simple of things. The sway of the golden wheat stalk in the afternoon breeze. The chorus of our young voices around a sparking bonfire. The frolic of our half-dozen heinz 57 mongrels as they tore through the fields and around our old, ramshackle trailers.

There was one particular girl in the community that took a real liking to me. Her name was Harmony. She was short and shapely, with emphasized feminine traits. She had strong and high cheekbones that centered on a cute button nose. Her forehead was beautifully rounded beneath her thick, long curly brown hair. I recall staring past her long fluttering eyelashes and into her deep hazel green eyes for hours on end. Our love was a youthful one full of immature childish voice acting, alter egos, as well as, playful inside jokes and analogies. She had a motherly affection for the world though she swore she wouldn’t ever be one herself. Her shy demeanour would blossom with a little watering from an alcoholic beverage or two.

We had a deep affection for each other but nonetheless knew of a lustful world beyond each other’s grasps. Of the women I had come to know, she was by far the cleanest and most orderly. I think it stemmed from her protestant upbringing and the fact that she was a mirror’s image of her mother who was a devout churchgoer and voluntarist. Though she rarely went to church herself, she saw the world through a lens honed by the pasture’s voice.

I could see it in her face that she held a deep shame in our intimacy. I thought that perhaps she was also a little embarrassed of my heathen bravado. Though I could honestly say that I was in love with her, it wasn’t long before she couldn’t say the same of me. This was yet another way the world seemed to be collapsing in on me during my most vulnerable of times. Like an animal backed into a corner, my ego inflamed as it fought her rejection. I was both heartbroken and angry. In the end, I tried to hurt her with my words, to make her feel small and unimportant. I would make fun of what we had together, what I used to find the most fulfilling. I didn’t want to accept it, and if I had to, then I wanted for her to have something to accept too. This vitriolic behaviour was the mark of a weak and desperate person. Looking back I feel ashamed and regret how I acted.

It would inevitably be this collision of influences that would make the bubble of my ego large enough to finally pop. I took the world personally and I was far from skillful about it. Beaten and bruised by what I perceived to be a world colluding against me, I was now on track to find my center, though I didn’t know it at the time.

It was there, in a spray-painted trailer, tucked into the back corner of an old wheat field that I had first heard of Tinando monastery. It was a new Buddhist monastery that had just opened to the public in our small, northeastern American town. Though I would spend the rest of the summer in a polyamorous melting pot of haphazardly placed trailers filled with young, happy, and free iconoclasts, it would ultimately fail to fill the void left by my time abroad. It seemed that my hands were then forced into a transition away from documenting the wars of the world, to instead, documenting the wars of my own mind.

The monastery consisted of an old white-pillared farmhouse, two large barns, a newly constructed place of ceremony, which contained a small mediation hall, and several tiny kuti huts where immigrant monks resided. The property itself was many acres; some field, some grass, and some forested. Sinuous pathways negotiated the hilly landscape where the monk’s kutis were quite arbitrarily scattered. In the fall, the property was overwhelmed by deer, birds, squirrels and a diverse host of other animals. The winter saw a decline not only in wildlife but also in visitors to the monastery. It was largely a time of self-reflection and meditation for its residents. By most, it was considered to be a time of retreat.

I was welcomed into this monastic community as an anagarika, this is the Pali term for homeless one. I had not propositioned to ordain but rather just to live there in the hopes of healing. My time there was initially indefinite, though I had a hunch that I may not be able to lock myself down for more than a few months. Though the monastery was the epitome of calm relaxation, monastic study, and self-discovery, my mind began contriving elaborate ideas of travel and adventure that I yearned to relive. Looking back on it, I was happier there than I had ever been before… or since, for that matter.

It was a magical place filled with the most wonderful people. We had a very structured day of chores, work periods, meals, and communal meditations. The environment was highly stress-reducing and the people were beyond accepting. Everyone there acted as skillfully as they possibly could and no one ever had anything negative to say, especially not of one another. It was almost eerie at first but I soon discovered it to be the foremost conclusion of how human behaviour ought to be.

After the war, my time at the commune taught me love, lust, and the difference therein. I was, however, still an unskillful person, well capable of selfish blindness and woeful indiscretion. It wasn’t until months into my time as an anagarika at Tinando that I really found myself shaping up. My mind had been given an environment in which it could heal, a place where it had no stress and no worries. It was there that I first learned the basics of the Buddhist path.

I learned to see my suffering, incompleteness and dissatisfaction with the world as a symptom of having a diseased mind. The cause of which was Tanha, which in Pali means “thirst”, this was the bodily analogy for desire, craving, grasping, and clinging. These things are creations of the mind, dispositions of the mind to the world and it is our own mind, therefore, that is the cause of our suffering. This realization is the prognosis, it is the understanding that cessation of dukkha, or suffering, is possible. The Buddhist cure was to follow the eight-fold path, which is essentially just a list of disciplines and efforts designed to hone one’s virtue, concentration, and wisdom.

There are three principle concepts in Buddhism which must be known firsthand for the development of insight. First, there is dukkha, as described above, it is suffering or unsatisfactoriness, then there is anicca which is best understood as impermanence, and lastly, there is anatta, or not-self, which has to do with fundamentally shifting one’s perspective away from that of an ego. It was impressed upon me that understanding not-self and living a life which reflects that understanding, is the greatest virtue of them all.

I can recall my first real lesson in Buddhism as if it was just yesterday. It was a simple one on one, sit-down with a Monk named venerable Khutibah on the 4th day after my arrival at Tinando. The following is what he told me.

“When turning to Buddhism, we must first recognize the fact that we all arrive here with the heavy burden of our past, our memories, and habits, as well as our great plans for the future. If Buddhism is to be the path for you, then it will certainly shake you free from all of this.

“Buddhism is the “ism” of awakening. To awaken is to cease to exist in a dream state. It symbolizes a move from a false state to a correct state. This is what Siddhartha Gotama is said to have done by way of achieving great wisdom through his own effort. At its core, the conventional understanding of life is inadequate, and to have this realization is to see the dream for what it is. Before a solution can be deliberately implemented in one’s life, there must first be an awareness of the source of the inadequacy. This is the enterprise around which the Buddha’s wisdom is erected.

“By becoming a Buddhist, you are in effect committing yourself to a lifestyle which promotes community, compassion, and generosity. This promotion corresponds to a demotion of the self and the circumstances of which the self is derived. This is the concept of anatta, that the self one perceives themselves to be, is in fact a transient feature of their broader consciousness.

“Now the first bit worth noting about Buddhism is that it is divided, both by geography and perspective, into three main factions or schools of thought. There is Vajrayana, the diamond vehicle of Tibet and Nepal. Then there is Mahayana, the great vehicle of Korea, China, and Japan. And lastly, there is the school that we here at Tinando monastery subscribe to, Therevada, otherwise known as the school of the elders, which still persists throughout Laos, Burma, Thailand, Sri Lanka, and Cambodia.

“Now, one must have a basic understanding of the Buddhist path. Get to know the three refuges of the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha. Respectively, they represent wisdom, truth, and virtue. You can imagine them as the teacher, the teaching, and the receptive ones. You see, the Dhamma is the oral tradition of the Buddha as chronicled by his disciples and the sangha is the community of followers; the monks, nuns and laypeople alike.

“For each of us as individuals approaching Buddhism for the first time, the path should be looked at as follows. You become a member of the sangha, the spiritual community of Buddhists, by accepting the ‘three refuges’ along with the ‘five percepts’, or the ‘eight precepts’. And by being an active member of this community, you cultivate self-discipline and virtue. The next pillar is that of meditation, which is the other side of the aspect of truth within the path of an active Buddhist. Where the Dhamma guides us, meditation is our personal discovery of the truths it describes. Lastly, there is the pillar of wisdom. It is the fruit of our practice and must be cultivated slowly and with persistence as we make progress with becoming virtuous individuals. So to summarize, as Buddhists, virtue, truth, and wisdom are the general qualities that we seek to develop.

“Let’s explore the idea of meditation some more. So what is meditation? At its core, it is the act of repeatedly refocusing attention on an object. When the mind is pacified, it is conducive to the broadening of our understanding of that object. Meditation is also a practice of detachment. It is a momentary release from our possessions, our thoughts, our circumstances, and the suffering that they derive.

“The most common object of meditation is that of the breath. Close your eyes, sit still, bring your attention to the breath, and in due course, lucidity and serenity will emerge. In this meditative disposition, our stresses, as well as our suppositions, can become discerned with more clarity and therefore are more likely to become subject to resolution.

“Mindfulness is a more versatile attention, one that can be maintained throughout daily life. By focusing of attention on our tasks and how they make us feel, we can make life’s activities our object of meditation. Mindfulness can also refer to our ability to keep something in mind as we move through our day. This is the sense of the word which we are referring to when we discuss the ‘right mindfulness’ of the noble eightfold path. It is to consider the occurrences of our life through the aperture of a specific context. It is to see the world through the deliberately elected framing of our choice. So for example, if one’s intention is to resolve to abandon unskillful behaviours and develop skillful ones, then they must keep these criteria in mind and consider each development as it arises in these terms. To be mindful is to be free from all-consuming doubts and worries.

“Now what of enlightenment? Awakening? Nibbana? Satori? Or As we westerners often refer to it, Nirvana of the Sanskrit? Well, most think of it as some state of mind that must be sought after for a lifetime before being achieved. That it is some magical state that transcends life as we know it. This is hyperbole. In fact, I would contend that we have all tasted it ourselves at one point or another. Nibbana is after all not something that we acquire but rather it is what already exists as the base layer of our consciousness. It is the way the mind is when it is no longer burdened by the habits and pressures of the ego. Extract the ego, even if just for a moment, and there, one will find the serenity and joy that come from detaching from circumstance.

“As for Buddhist Wisdom, well there isn’t all that much that I can offer you apart from recommending that you read the Dhamma. I can however outline the general direction that Buddhist wisdom leans towards. You see, ultimate-truth is less prevalent due to the fact that claims of this sort lead to division, argumentation, and in some instances, where the parties are unwise enough, even violence. Buddhist wisdom instead describes what one will come to know about life, through practicing meditation and virtuosity, under the guidance of the Dhamma, and without having to accept any particular beliefs.

“I Came to a realization some years ago. That being that it occurred to me that what was most important was the magic of the mystery and a greater life purpose. I needed some sort of higher calling, one that satiated my mind in all of its aspects. One that helped others and served the greater good. For me, that was ordaining, becoming a servant of the Buddha and the Dhamma.

“I am incredibly grateful for the forces that brought this to fruition and I have never been happier. When the Buddha was asked why his followers all appeared so joyful, he responded that they, like himself, had forgotten the past and lost their concern and speculation for the future. He continued to explain that because of this, they resided in the present moment and were therefore free. In their radiant freedom, they were no longer attached to any particular mental or physical phenomena, and that their serene joy was the fruit of their independence from circumstance.

“Without monks, the three refuges are incomplete, unviable. We act as spiritual companions for all those on this path. We unambiguously represent the values of the Buddha and his Dhamma. We support the lay population and they can achieve their merit and develop their generosity by supporting us. We all have our roles within our communities and society as a whole. The role of the monk has many folds but I like to think of us as beacons of compassion in a world starved of it. With the four sublime attitudes, that of limitless goodwill, compassion, empathetic joy, and equanimity monks act as a counter, or opposition to those of immense wealth who remain greedy, those of immense fear who remain mean, careless, and destructive. Monks are a beacon of hope in a world of confused conventions.

“With the above said, I think there is nothing more important to teach a new interest in Buddhism than that of the four noble truths. There is ‘the fact of Dukkha’, ‘the origin of Dukkha’, ‘the end of Dukkha’ and ‘the path to the end of Dukkha’. Come to know these simple truths and you will find your inner serenity. That I promise you, my new friend.

“The Fact of Dukkha…”, he began.

“Firstly, and as you likely already know, Dukkha is a Pali term which translates to English as something along the lines of dissatisfaction, unsatisfactoriness, suffering, or stress. Secondly, note that the conventional understanding of life is not adequate as it necessarily leads to a large portion of our life experiences being unsatisfactory and stressful. Life as most know it is riddled with traps and inevitable negative eventualities. Buddhism not only helps us avoid these traps and pitfalls but also preferably orients our perspective to better deal with these sorts of unavoidable negative events.

“The Origin of Dukkha…”, he continued.

“Our suffering has a handful of origins. At the center of all is the concept of desire. We have our attachments, conscious or otherwise and these dictate to what we grasp or cling, as well as what constitutes our aversions. Our desires define what push and pull us. They are false motivations. In fact, they all lead to suffering, even when we find ourselves in agreeable circumstances, they ultimately will prove to be vulnerable and transient. This is the concept of Anicca, a Pali term for impermanence. Desires achieved upon false motivations are like houses built on sand, their foundation is shaky and inevitably impermanent. In short, even when things go our way, are enjoyable, and appear positive, they will ultimately result in a sense of loss. This is the fate of those who seek fulfillment in that which is impermanent. This is the concept of anicca.

“You see, not getting what you want is dukkha… and even getting what you want eventually leads to dukkha… therefore wanting, in general, is dukkha. Forget what you think you desire, what you actually desire is a relationship with the cosmos of peace and understanding. Illness, aging, pain, and death are inevitabilities of life. So the question is, how can one approach life in a manner that does not derive unnecessary stress and anxiety from these formalities? How can one save their diminishing sense of purpose? The answer…

“The End of Dukkha…”, he squeezed through his smirk.

“The more ego one has, the more vulnerable they become the barbs of the world. Just as flesh gets caught on metal barbs, the ego gets caught on mental ones. So long as there is an ego within, pulling the strings and evaluating our world of experience, there will be dukkha. Therefore, one could say that the end of dukkha is contingent on the release of not only our ego’s habits but also its perspective. The ego is the mechanism by which we attach ourselves to circumstance. 1- Achieving Nibanna, that being a happiness and inner peace that exists as independent of circumstance, and 2- the dismantling of one’s ego, are largely one and the same proposition.

“The mark of the beast here is the emotions of pride, and shame, along with the vicissitudes of pleasure and pain, gain and loss, praise and blame, as well as, fame and disrepute. These are the limbs of the ego and to cut them off is no small task. It must be fostered slowly and with care. As one’s generosity begins to exceed their greed, as their love exceeds their hatred and their wisdom exceeds their delusion, they are lessening the presence of their ego as the mediator of their experience.

‘“Let me reiterate… regarding pride, shame and guilt… the degree to which one harbours these emotions is precisely the degree to which they are identified with a small sense of self, the degree to which they are in the grasp of a self-feeding and self-serving ego, the degree to which they are falsely motivated. At base, to have an ego is to be driven by a false narrative. It is to be blind to what actually is, and by extension, ignorant of what actually matters.

“So what does the end of an ego look like? It will lack pride and shame. It will not consist of pleasure and pain, gain and loss, praise and blame, or fame and disrepute. It will not display clinging or repulsion, desire or aversion. Its greed will dwindle in the flame of generosity. Its hatred will drown in the ocean that is its all-encompassing love. Its delusion will be resolved into the light of its wisdom.

“When one is no longer falsely motivated by their ego and its pursuit of fulfillment in that which is impermanent, one may become available to the splendour that is living a more spiritually-attuned life. The Pali term for this concept is samvega, which is a general dissatisfaction with the purposelessness many find while living a conventional lifestyle. The spiritual enrichment of one’s life opens them up to a world of unshakable fulfillment and a life of greater purpose.

“Lastly, the fourth noble truth, the Path to the End of Dukkha…”, he carried on.

“This path represents the journey to the cessation of our worldly stress and suffering. It requires only that we know of it and have the persistence and wisdom required to accomplish it.

“The noble eightfold path. In Buddhist iconography, symbolized by a wheel with eight mutually supportive spokes, each in place of a percept, is the defined way to this release from dukkha. They are as follows: Right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. Where their qualification as ‘right’ pertains to their directionality away from self-centered habits and instead to harmony with the virtue, truth, and wisdom of the Buddhist path.

“Allow me to quickly go over each…

“Right view, to see experience in terms of the noble truths.

“Right intention, to resolve to abandon thoughts of sensuality, ill-will, and harm.

“Right speech, to abstain from telling lies, speaking divisively, speaking harshly of others, and partaking in idle-chatter.

“Right action, to abstain from killing, inflicting harm, stealing and participating in illicit sexually behaviour.

“Right livelihood, to not make a living out of something which is dishonest and or, harmful.

“Right effort, to resolve to abandon unskillful behaviour and the develop skillful behaviour.

“Right mindfulness, to keep attention focused thoroughly on the task at hand without distraction and also, and more importantly, to keep right effort in mind throughout the course of daily life.

“Finally, there is right concentration, which has to do with the four levels of Jhana meditation that the Buddha achieved beneath the bodhi tree at the time of his enlightenment.

“I know this can all be very overwhelming at first glance but I promise you that there is a brilliant life awaiting all who accept this challenging method of development through the noble eightfold path. For now, here is a shortlist of mantras that you can memorize. They contain much of the sentiment I have discussed here and will help to orient you on your path.

He handed me a folded piece of paper, its edges were aged, slightly browned, and worn. Upon opening it, there, written across its deep folds were the following lines:

“-If you know what is wrong, foolish and unworthy, what leads to harm and discontent, then abandon it. If you know what is right, good, virtuous, and wise, then develop it

-During times of difficulty, serenity and patience are within me

During times of good fortune, compassion and generosity are within me

May my mind and heart stay steady and buoyant throughout all of life’s circumstances

-May my generosity exceed my greed, my love exceed my hatred and my wisdom exceed my delusion

-I will be mindful of the origins of suffering; desire and aversion, impermanence and unfavourable circumstance

-The vicissitudes of pleasure and pain, gain and loss, praise and blame, pride and shame, as well as, fame and disrepute are the ego’s limbs

-The development of compassion, patience, and service are my methods

-My body is a temple in which resides a skillful and cleanly mind

-My purpose in life is to love, nourish, nurture and assist others for they are I and I am them, together we are one

-I am happy, I am healthy and life is good, as I am immersed in a beautiful world. The world is beautiful as it consists invariably of inevitable conditions

-I cultivate non-resistance, non-judgment, non-reaction, and non-attachment”

It was the confluence of many factors that soon had me on a plane to Fukui, Japan. I had the pain of my past, a couple of consequential and failed love affairs, as well as that which still haunted me from my time as a journalist of war. I had the urge of wanderlust fuelling my departure, the thrill of the mysterious yet awaited me and I could feel that deep within. The whole adventure was motivated by my time at Tinando. I wanted to pursue Buddhism but I knew that being yet another layman wasn’t going to be enough for me. On the other side of the equation, I knew that ordaining as a monk was a step further than my desire to travel would allow me to take. And so it was settled, I would sell what few possessions I had left and board a flight to Japan to begin my hunt for the Buddha incarnate. Later I would find myself journalling all over Asia; Japan, Thailand, rural China, India, and Nepal.

Pt. 5: The Bonsai of Impermanence

The morning of my flight was an exciting time as it once again stirred my sense of adventure. I was headed to Fukui, a quaint and budding city about three hundred miles up the northwestern coast from Hiroshima. Nestled between the mountains of Ryōhaku and the sea of Japan, Fukui existed as a modern economic development built atop an ancient structure rich with Zen and Samurai history. It was a great example of how quickly times can change and the ingenuity of man can progress. Like moss over a stone, the modern structures of our time paint the earth’s surface only to ultimately crumble back into it.

Being so close to the site of the Hiroshima bombing, I could not help but ponder it. It was about 35 years removed and yet to me, as a foreigner, it felt so fresh. A single atom bomb, delivered by a handful of operators in a B-22 bomber, killed an estimated 80,000 people upon impact and tens of thousands more later from residual radiation exposure. If that wasn’t enough, they repeated this horror in Nagasaki. This unconscionable loss really puts the fragility of life into perspective, that it can indeed be taken away in a literal flash.

My first love gifted me a brown leather-backed notebook, it was no bigger than the spread of my hand. I had many possessions that I could leave behind but this wasn’t one of them. I had no intention of writing in it, it was more of a keepsake. Little did I know that the notebook’s sentimental value would make it all that much more conducive to capturing my emotions. There was a higher standard for what my pen’s ink would bleed into its pages. The book meant too much to me to be filled with my usual rubbish. I reserved it for truly inspired moments. There, in that airplane, over the loud roar of its engines, I wrote my first entry in my beloved book. Each pen stroke was especially tidy and deliberate.

“The tree inadvertently arranges its form into a complex of entanglement. And so, in this form, its lower branches do not hesitate to catch and hold any such limb which should fall from its higher regions. Much in the same way, when the mind experiences loss; be it the death, rejection, or the passing-by of a loved one, its attachment exceeds its permanence. And so, the mind is left in a state analogous to that of a tree which has suffered a lightning strike, it captures and arrests the dismembered appendage on its journey to the ground. The larger the branch, or the more consequential the person, the more likely it is to become entangled in the edifice below. We grasp onto the remnants of our losses, we grip the artifacts of the past and in doing so, we fail in returning them to the ground from which they grew. Though a detached branch may be released from its entanglement by a sufficiently strong wind, the tree does not have the capacity to voluntarily let go. While on the other hand, the mind, when faced with impermanence, has no other option than to exonerate itself. For it is the earth from which all relationships grow and it is the earth to which all will return; to decay, to be reclaimed, and to one day re-amalgamate as new life. One must remember that it is the ethereal nature of life that gives rise to the dynamics of change and novelty, and thusly allows for us to ephemeralize our world. To cling to the past is to be static and to be static is to be dead. All life emerges from its own impermanence“

The funny thing about suffering is that it is both a product of the ego and also the greatest tool for penetrating it. Most commonly, suffering is a trivial, surface-level scraping of our identity. The ego is so fragile and responsive that it can build itself up in its own defense. While this is true, deep suffering can be so consequential as to uproot the ego entirely. Losing a loved one can be like being a musician who loses his ears, or an artist who loses their eyes. Romantic love, when we are immersed in it, can taste like nectar and feel like sunshine. Losing this can cause a person to broaden the scope of their awareness as they retreat from pain. Eventually, it can erode one’s identity, their ego, entirely.

Japan is home to the relatively strict Buddhist practice of Zen. At its core, Zen is a Mahayana fork of Buddhist philosophy. This branch is called the great vehicle and is considered to be the most stringent of all Buddhist practices. Zen focuses on direct engagement with reality and views thought as a barrier to it. If the mind is to be broken down into two basic categories, they may as well be that of sense-perceptions -the qualia of consciousness itself, or rather, how it feels to be you- and those of thought-perceptions -the mind and its contents as they are constituted in their semantic nature-. Zen Buddhists feel that if we are to best understand reality, that this cannot be achieved through the misleading conceptual scaffold of logic and language. In principle, life must be experienced directly through the senses to be understood. The more closely one can connect with their senses, the closer they come to reality itself.

I was headed to Eihei-Ji Temple to study under the great Zen Master Sanshoho Daibutsuji. The Mahayana Buddhist mindset is one of compassion. So much so, that even when enlightenment is achieved, a Mahayana master will choose to be reborn into the samsara that is human existence in order to help those less fortunate achieve enlightenment as well. My logic was that if anyone was truly enlightened, it would be one of these returning Mahayana Masters. If the Buddha was to still walk the earth, he would certainly only do so to help others find their way beyond the cycle of rebirth and unenlightened lives. Master Daibutsuji was my safest bet, “surely he was the Buddha”, I thought.

I took a taxi from the airport straight to the front gate of Eihei-Ji. Through a rain-speckled window, I could see the beaches and cliffs where the land sank beneath the sea of Japan. The beginning of the ride took us through the heart of the Fukui metropolis and before I knew it, we had emerged at the sparsely populated rural mountain landscape of Ryōhaku.

When I arrived at Eihei-Ji I was greeted by a lone monk at the gate, he instructed me to wait for Master Daibutsuji if I wanted to enter the Temple. As he turned away, he winked and motioned for me to sit on the bottom step of the grand staircase he then slowly ascended to the temple’s entranceway. So I did, I sat and I waited. And I waited. And I waited some more.

It was a dismal overcast day. You know, the kind where the sky is grey, everything is ten shades darker than it should be and covered in a reflective wet sheen. The kind of day where the mountain mist is so heavy that you might as well be in a cloud. Everything was through-and-through wet to its core. The soaked and drooping leaves of the forest shimmered with sedated water droplets developing at their bases. I felt as if I had been submerged into the fog, it was more of an atmosphere than I typically credited Appalachian fog with. You could see the infinite suspended droplets in the air as they delicately floated to the ground in unison. It was the wettest day of my life.

I sat through the day and then through the night. I was too wet to sleep and too cold to meditate. I recall a deep frustration welling up inside of me. Was I being played? Was this their way of telling me that I wasn’t welcome? Was it because I was a westerner? If it wasn’t for the fact that I simply had nowhere else to go, I likely would have stormed off in anger and never returned.

Before I knew it the sun had risen and the cool dampness was lifted. The sky illuminated everything with a rose gold hue and I suddenly felt all of my resentment fading. If it weren’t for the fact that I was physically shaken out of samadhi by the bony hands of a hurried monk, I wouldn’t have even opened my eyes when the monk returned to collect me.

I didn’t know it at the time but it was customary to be left alone outside of Zen temples, for a day’s time, before they would consider granting you entry. It was their way of weeding out the undisciplined and impatient. Zen is, after all, the most strict and restrictive of all branches of Buddhism. If they just left the doors open, they would have nearly as many people leaving as they did arriving. It was no small task to stay the course with a real Zen Master.

The Monk who retrieved me was named Manny. He was a tri-lingual English and French teacher from the north of Japan. He was the only English-speaking monk at Eihei-Ji. Not that we did much talking at the temple but it was nice to have someone to translate for me occasionally. Though I fell in line with the daily activities of the Monks, I was very much so left to my own devices mentally. Unlike the monks at Tinando, no one here was holding my hand and giving me mental instruction. We did about 5 or 6, or maybe, 7 or 8 hours of meditation a day. To be honest, It was hard to tell because I didn’t have a clock for the entire length of my stay. I simply woke when the monks ran down the hallway beating a drum and stick. This wake-up call was not to be taken lightly, anything less than jumping out of bed was frowned upon. Then we meditated for some unknown but lengthy amount of time before cleaning everything as if it had never been cleaned before and eating a very modest rice, tofu, and vegetable broth breakfast. This breakfast was our only meal for the day and after it, we would return to meditation.

At Eihei-Ji, the mediation hall was literally a hallway. On either side, there were elevated platforms that ran its length. These platforms were where Monks sat for Samadhi and also to eat. Divided by the Master’s pathway down the length of the room, monks sat facing each other but never looked at each other. Monk’s eyes were always either closed or looking at the ground a few feet in front of them.

During meditation periods, it was of the utmost importance that you sat with the best possible straight-back posture. Holding a large bamboo stick, Master Daibutsuji would pace up and down the length of the meditation hall. The soft shuffle of his feet was mesmerizing but heaven forbid you heard them come to a stop in front of you. For more often than not, this was followed by the loud howl of his hollow bamboo shaft as it swung through the air to strike your shoulder. This being the consequence of slouching or falling asleep. The crack of his corrective tool would leave marks of red and could even draw blood.

Though hardly a word was shared with me, my stay at Eihei-Ji taught me many things. The discipline of routine. The simplicity of non-indulgence. The calm of stilling one’s mind. The beauty of silence.

Manny would accompany me to my meetings with Master Daibutsuji. This is where he would silently evaluate our progress and deliver a fitting Zen koan for us to ponder until our next meeting. I would tell Sanshoho what conclusions his last koan lead me to and after Manny translated, Master Daibutsuji would sit silently for a moment or two, deeply staring into my eyes before responding with yet another koan. This made up the entirety of my exposure to Sanshoho. If he wasn’t hitting me with a stick, he was giving me an impossible puzzle to ponder, or at least that was what I thought at the time.

The Zen koan is a tool designed to provoke doubt within an individual’s mind. The mind will attempt to answer the riddle logically but ultimately what logical prowess it has will be built atop a shaky set of underlying assumptions. Assumptions represent a lack of knowledge, and or, information. An honest mind will see this deficit and a great doubt will arise within it. This “doubt”, shifts attention away from the analytical apparatus of the mind and towards that which can be known, without doubt, our direct experience. At least, this is how Sanshoho Dabibutsuji described the koan to me. I recall him saying that, “Most people are like a numb arm stuck through a hole in a wall, blindly probing around in an environment they are failing to sense or experience.” Surely, this is hyperbole. Of course, we sense our surroundings, of course, we come to know our environments. The point is not to paint a black and white landscape here, but rather to describe the degree to which our mental noise and fictions can distract from what is right in front of us. Just as a spoon can stir sugar into coffee, the koan, in a far more complex way, stirs life back into our hearts.

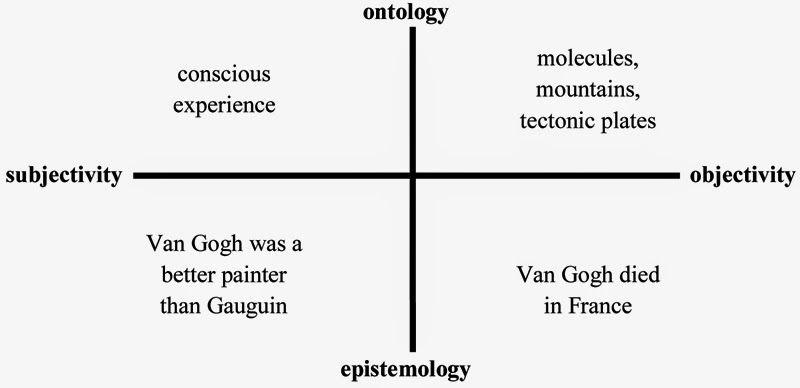

My favourite of Sanshoho’s koans went something like this, “What is the sound of a tree falling, if nothing or no one is there to hear it?”. Well, the logical mind says that if there is nothing, or no one there to hear it, then it doesn’t make any noise at all. Sound is an auditory experience, it requires ears and a whole central nervous system to produce it. Sound is ontologically subjective. Now, what does that mean? It basically means that its existence is dependent on a consciousness to host it. In other words, sound is observer relative. So what does the tree make when it falls? It makes pressure waves in the air, these pressure waves exist out there in the objective world whether there is a central nervous system present to interpret them as sound or not. Therefore, these pressure waves are ontologically objective and observer-independent… No observer? then no sound. No perceiving awareness present? Then nothing can be perceived.

While this logic and reason approach to understanding reality serves its purpose in many regards and on many fronts, Zen practitioners emphasize coming to understand reality directly through experience itself. Explanations offer a semantic understanding, whereas direct qualaic experience, or rather, the world as it penetrates our senses, offers a tangible one. If one’s goal is to achieve a greater sensual awareness, that being, a deeper connection with their experience of the here and now, then facts and knowledge-based understandings, as well as, our subjective interpretations of the world, can in many regards, act as obstacles to this enterprise.

Manny and I would spend our late afternoons in open-eyed meditation in the garden. At Eihei-Ji, there was the most beautiful of Japanese gardens. It was full of grand hinoki cypress, vigorous Japanese maple, strong sacred bamboo, and beautiful pink, kwanzan cherry. At the heart of it, there was a small rock garden of raked gravel that circled around 5 prominent and unique boulders. During the morning chore period, this garden would be raked slowly and deliberately, as if it were being massaged by the long tongs of the oak appendage. Not only did it tidy things up and remove fallen debris but it was also done for its symbolism. It represented impermanence, dynamism, acceptance, and appreciation.

It fell upon me to rake the rock garden a handful of times. I wasn’t particularly good at it and I didn’t paint a particularly beautiful landscape but I definitely tidied it up well. Raking the garden ingrained in me a love for the tedious. Picking the fallen peddles of the pink kwanzan trees from between the tiny stones became an exercise in futility that would follow me for the rest of my life.

Like all things in the garden, there was a frail arch bridge that seemingly served no purpose, to the untrained eye, it went nowhere. It simply popped up from the ground in one location and sank back into it in another. It was only about 20 feet long and it crossed over nothing save a small patch of well-manicured grass. One of my most vivid memories of my time in the garden is of Manny describing purposelessness to me. He said, “That bridge, it goes nowhere, it circumvents no obstacle, no one has any expectations of it nor does it expect to be utilized by anyone. And yet, it is. You see its purpose is of a higher order, it has a… higher purpose! You see, Its purpose is to teach purposelessness! Some men walk the path to arrive somewhere, while others walk it to arrive nowhere. Some women do things to achieve something, while others do things to achieve nothing! When I listen to Japanese flute, I don’t expect any destination to be arrived at, I simply enjoy the journey of it. When nature grows, it doesn’t expect to grow into any particular end form. Do you think the eons and eons of waves lapping on beaches have any meaning? Nature is purposeless. It carries no intention and has no goal, it simply is. I myself, well I… I strive to embody that principle, to be like nature, to be purposeless!”

Looking back on it, Manny strived to be purposeless, so that he too, like the bridge, could teach purposelessness, this was his purpose and it was this, in and of itself, that was the primary reason that he was failing to reach his goal, it was the mere fact that he had one at all. He needed to drop his intentions and become like the eons and eons of lapping waves, of anicca.

Pt. 6: The Lotus of Ten-thousand Folds

My next stop landed me in Chiang Mai Thailand. I was tracking down the most venerable of Theravada Monks, Ajahn Chah. Theravada is the school of the Elders and Ajahn Chah was indeed the oldest and most noble of the Thai Buddhist elders of the forest tradition. Where Zen monks aimed to perpetuate life and use it to help others escape the cycles of reincarnation, the school of the elders was one that recognized their leaders as those readiest to graduate from the samsara of incarnation. With that said, I thought that this would be my only chance to study under the great, venerable Ajahn Chah before he ceased to reincarnate.

From the airport, I was taxied in a small cloth-topped Suzuki sidekick to the base of a mountain just beyond the lights of the Chiang Mai skyline. The moon was bright and full, casting a smooth yellow-white brilliance over the crowns of the mountain landscape. The ride was rough and I often found myself bouncing out of my seat in sync with the beat of the Thai kantrum music playing softly over the radio.

Ahead on the road, I saw three Robed monks strolling up the mountain. I thought they must be headed to where I was going, so I instructed the driver to pull over. To my surprise these men were caucasian, clearly, they were westerners like myself. As I reached back into the cab of the truck to grab my backpack, I began introducing myself to the monks. They responded with their names, followed by a quick raise of their clasped hands to their foreheads and a slight bow in my direction.

Their names I would never forget. There was Viradhammo, Sumedo, and Jack. Over the course of our stroll up the mountain’s side, I would quickly come to learn that they were all incredibly intelligent and wise for their young age. The three of them wore wide smiles as they told me about Ajahn Chah’s brilliance and leadership. They joked about how the white of the anagarika robe was near impossible to keep unbesmirched, especially with all of the outdoor chores I would have ahead of me. But they assured me that I had come to the right place if I was hoping to learn of Dukkha and its cessation.

I was awakened by the warmth of the morning sun on my chest. Behind closed eyes, the Thai sun crept in and slowly penetrated my dream. I was holding my first love, squeezing her so tightly that every muscle in my body was violently quivering with the contractions of an absolute and total emotion. As she faded into the wash of the blinding light that entered my opening eyes, I knew that I would be carrying into my day, the emotional pain of missing her. The pain of having to let go of her embrace once again.

I was sharing a hut with Jack and this was my first morning awakening to the song of the Thai birds. The summer mugginess of southern Asia’s tropical climate was something that I had not experienced in years. It thrust me into a series of flashbacks, some of Cambodia and some of Vietnam. Needless to say, I wasn’t having the smoothest of mornings. I seemed to be tripping over an unusual amount of hang-ups, my emotional memory was both triggered and inflamed.

As I sat up in my bed, I could see that Jack’s was both empty and made with the tension of a military tuck. Before me was the horse stall, half-door of the hut’s eastern facing side. Beyond it, I could see the sun bleached straw thatching of the hut’s roof as it descended upon a lush and vigorous, green vista. There was a fragrance of blossoms on the air, like that of a blissfully scented garden. At my feet were my whites and after dressing, I turned to find the silhouette of a small-statured man standing just beyond the closed half-door. With shock and surprise in my voice, I uttered a tepid, “hello… good morning…”.

With a chuckle, the man used a come-here motion with one hand as he pushed the door open for me with the other. As I stepped out of the hut, the small man’s silhouette bloomed with the detail of a thousand colours. As I walked past him, It occurred to me that this was none other than Ajahn Chah himself. His small body radiated a tremendous aura, not only of joy but also of kindness. He wore a brilliant smile, it was absolutely contagious and now I understood why the three monks I had met on the road had such eccentric grins.

“Your heart young Ana…” as he would call me, “We will train it to forget your self-centered habits!” He said enthusiastically. “Each and every day…” He continued,